1985 was the peak of the digital gauge clusters. When digital gauge clusters were introduced with the Aston Martin Lagonda in 1976 they were a luxurious feature. However, by the early 1980s, Toyota already launched their Soarer with a similar digital gauge cluster. Toyota being Toyota, copied their new technology to other upmarket cars like the Chaser, Cresta, Mark II, Celica, Carina and Corona. Soon other brands, like Nissan, followed suit and also featured digital gauge clusters in their top models. By the mid-1980s these digital gauge clusters had trickled down to even the smallest commuter cars like the Honda City and the Nissan March. The gauge cluster of the Nissan March is what we feature today!

Nissan March history

Let’s first dig into the history of the Nissan March. In the 1970s, the Nissan Cherry was the smallest car Nissan would offer. The Cherry grew in size every generation and by the late 1970s, it moved up from the A segment to the B segment. Nissan decided it needed a replacement for the void that the Cherry left and thus launched the March in 1982. Outside of Japan, we know this car as the Micra, but in Japan, it is called the March.

The competition of the Nissan March

The Nissan March was supposed to go head to head with the Honda City, Daihatsu Charade, Suzuki Cultus (Swift) and Toyota Starlet. These are all small cars in the A segment that are just one notch above the Japanese Kei class. The March launched in 1982. With the March, Nissan had an excellent proposition as it offered a lot of room for such a small car.

However, they were taken by surprise when Honda updated the Honda City with a turbo and made their car a little pocket rocket. This meant others quickly followed and also slapped a turbocharger on their engines. This caused these cars to deserve their own class and are called the superminis.

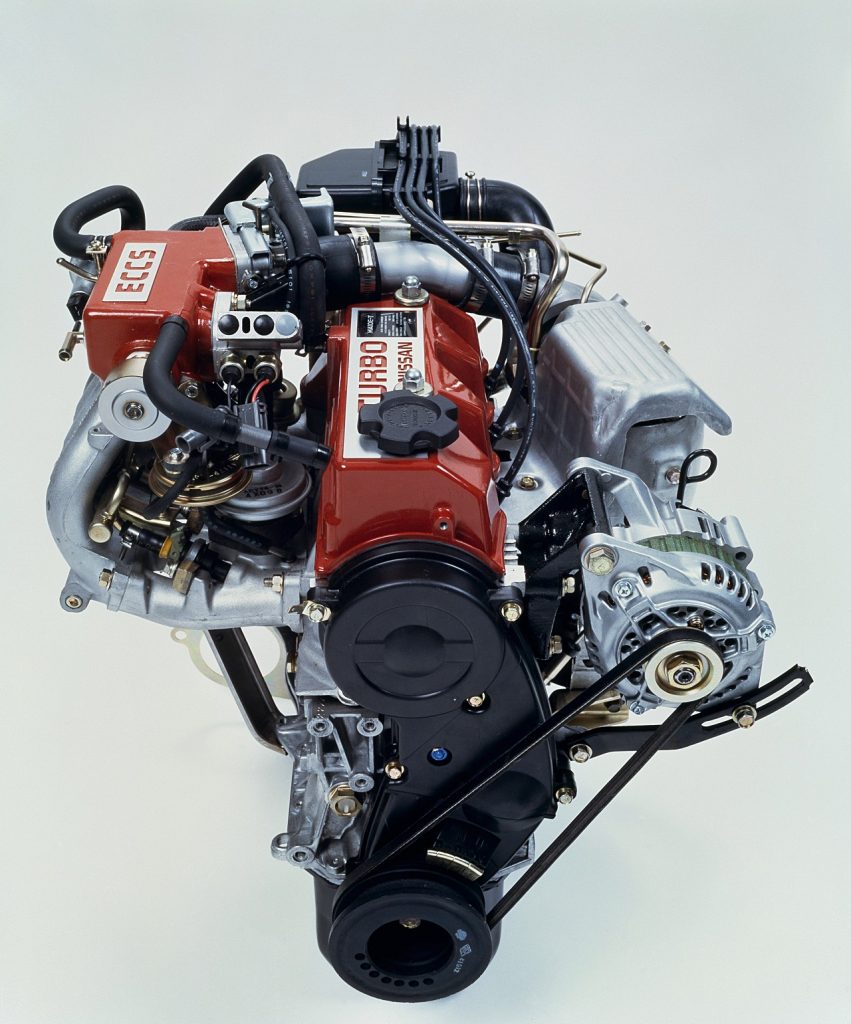

Slapping a turbo on the MA10 engine

Nissan also slapped a turbocharger on their MA10 engine and launched it in 1985 as the Nissan March Turbo. The new MA10ET engine made about 84 hp at 6000 rpm and 118 N⋅m; 87 lb⋅ft at 4400 rpm.

The Nissan March K10 platform was also used by Nissan as a basis for most of their Pikes cars. The Nissan Be-1, Figaro, Pao and S-Cargo are all using the same March K10 platform. However, the Nissan Figaro is the only one of the four Pikes cars to use the MA10ET engine.

In 1988 Nissan even went beyond the MA10ET by adding an additional supercharger to the engine. This was necessary as Nissan tried to enter rally competitions with a Nissan March. For this, they needed a homologation model and therefore they built 10,000 homologation March Super Turbo cars. But I digress, we’re talking about the March Turbo today. Not the Super Turbo.

Turbo interior and exterior

The March Turbo obviously also had to show it was a turbo model. Nissan didn’t go wild with all the turbo badges as Nissan did with the Nissan LePrix. The March Turbo is relatively low-key with only a couple of discretely placed turbo badges on the rear. The interior is a whole different story: the sports seats shout TURBO all over the place.

However, when you drive, you don’t look at your seats. So Nissan made sure you wouldn’t forget you’re driving a March Turbo! How? Well, like this:

On the steering wheel, you get reminded that you’re driving a car with an MA10ET engine with a TURBO. Not only does it feature the statistics of the engine, but you also get a small graph with the power curve of the engine. And you can’t push the power curve for the horn like you would do in any other car. No, you have to push below at the bottom!

Confusing and useless power curve

Another confusing thing about this power curve is why Nissan put it on the steering wheel. You could argue that it is there for the driver to know where he/she could expect max power and max torque. Like a good driving aid. However, Nissan omitted to print the rpm below the scale. Does this mean the driver has to count the number of lines to know where the maximum torque would be? Imagine you’re driving and all of a sudden you drive on a steep incline. Now is the time to shift down, get to that maximum torque and stay there. Let’s count on the centre of the steering wheel: “one…two..three..four…five…no, somewhere between four and five…4500?…no…just below 4500…yes, definitely 4400 rpm!”

As you see, it’s totally useless. The driver will never have the time to do the lookup. It’s a nice but useless thing on the steering wheel. It will serve no practical purpose or whatsoever, but it is cool as heck to have it on your steering wheel!

The hybrid gauge cluster

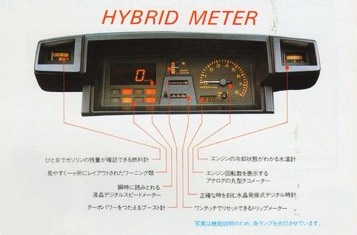

So now we move our attention to the gauge cluster. This means we now finally get to the question I put in the blog title: why did the Nissan March Turbo have a hybrid gauge cluster? And you may wonder where this hybrid meter comes from. Well, I found it in the 1985 Nissan March brochure:

As you can see, it reads “HYBRID METER” on this page. Here it is a little bit larger: (I’m sorry, but this is the largest picture I could find)

So what’s this hybrid then? Well, the gauge cluster only has a digital speedometer and a digital (quartz) clock. All the other gauges are analogue. You can see a boost gauge present on the cluster. Just like the fuel and temperature gauges have needles that move horizontally, it has a needle that moves vertically. You can also see the tachometer, which is a needle that pivots in the centre. The odometer and the trip meter both are analogue as well. So what does this mean?

It could mean two things. Either Nissan was too cheap to actually make the entire gauge cluster digital, as Toyota did on various models. This would have the implication also fuel levels and temperature sensors would have to send digital signals. This would drive up the cost significantly in the mid-1980s.

The other reason could be that Nissan deemed the digital gauge clusters too slow and too laggy. Customers would complain their tachometer would lag. Customers would complain their boost gauges were too slow to update. Which one it is, I don’t know, but both would be viable reasons why they did this.

Photos are all Nissan press photos, except for the brochure scan. Naturally the latter is also copyrighted by Nissan.

Very nice car, simple and it’s beautiful. Why is not available this days?